Silenced and Shut Down: How Lorain Council Ejected a Citizen and Looked Away

When rules are applied arbitrarily and critics are silenced, democracy disappears. This is the story of a council that enforces decorum selectively and punishes dissent.

By Aaron Knapp

Aaron Knapp is a Lorain-based investigative writer, advocate, and community watchdog. He publishes under “Lorain Politics Unplugged” and reports on corruption, civil rights, and government accountability throughout Northeast Ohio.

Legal Disclaimer:

The information in this article is based on public records, firsthand documentation, and constitutional analysis. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not constitute legal advice. All individuals named are presumed innocent unless proven otherwise in a court of law. Where criticism is levied, it is based on verified conduct, public duty, or policy enforcement, and not personal character.

I. A Moment of Civic Engagement Cut Short

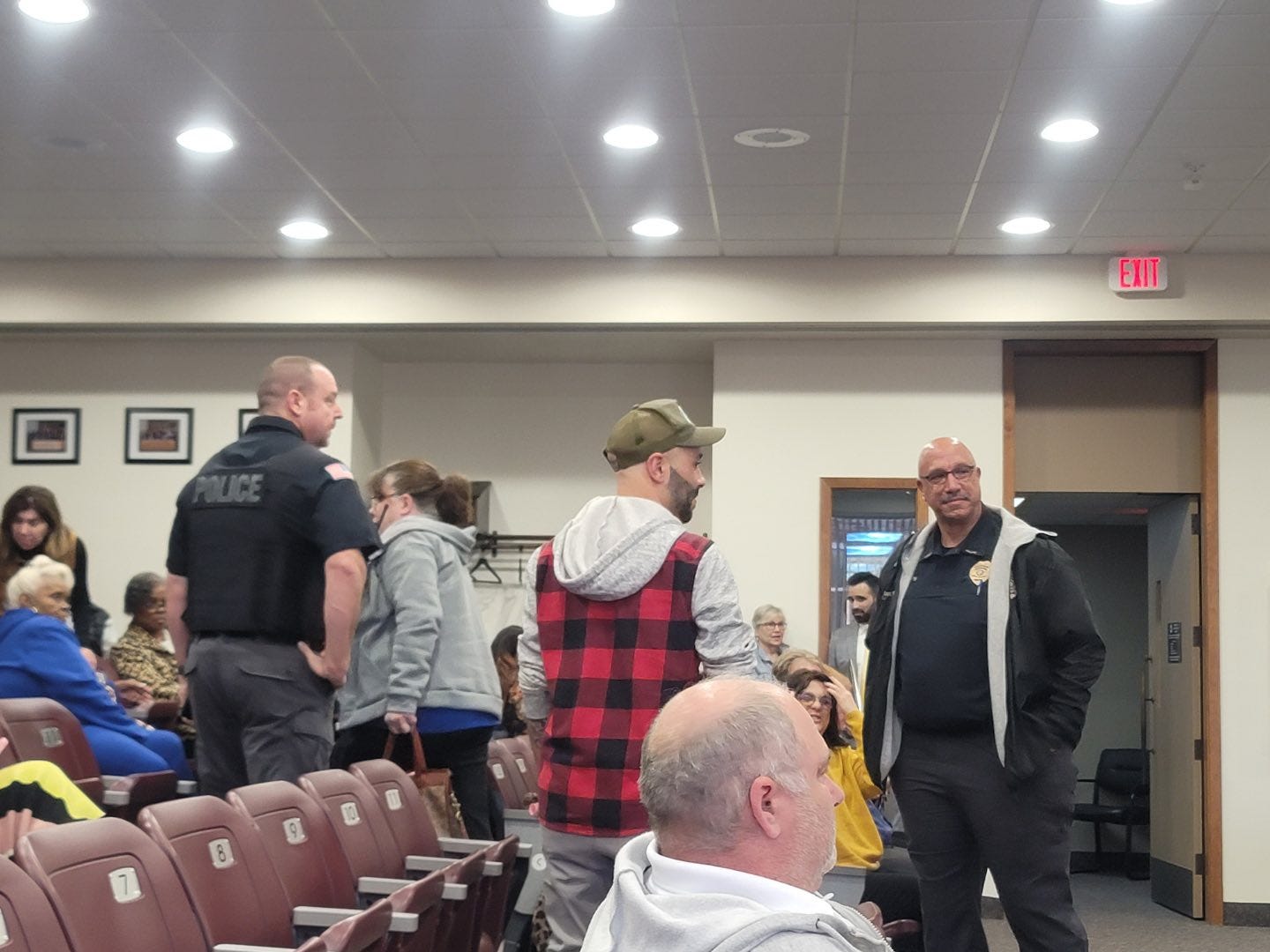

On May 5, 2025, Lorain City Council held what should have been a routine meeting. Instead, it became a case study in unequal treatment, procedural breakdowns, and the silencing of a citizen. During public comment, longtime resident Jayne Morales attempted to address the council about crime and the city’s failure to show up at a recent town hall.

Within seconds of beginning her remarks, she was interrupted by Council President Joel Arredondo: “Mrs. Morales, point of order—according to public comment guidelines…” he began, citing rules about not addressing individual members. Morales—passionate but civil—was swiftly shut down and ordered to leave the chamber.

“I asked for that town hall,” Morales said, referring to the April 29 forum on public safety. “We begged Tony Dimacchai to do that town hall.” Her frustration was clear, but her remarks were rooted in public concern. She used no profanity. She made no threats. Yet she was removed for speaking the truth as she saw it.

Joel Arredondo’s rigid invocation of speaking rules, coupled with enforcement that followed, transformed a moment of community engagement into a public ejection. While council rules state that comments must go through the chair and remain civil, Morales did not violate these in any substantive way. Her remarks were not personal attacks—they were criticism of government performance. But in Lorain, criticism is often confused with disruption.

“You work for us,” Morales declared as she exited. It was not defiant—it was democratic. Yet instead of engaging, council members recessed the meeting and returned only to reiterate rules, not to reflect or apologize.

Earlier in the meeting, the tone had already turned aggressive. Councilman Tony Dimacchai directly challenged Mayor Jack Bradley’s absence from the same town hall Morales referenced. Dimacchai accused the mayor and city officials of trying to sabotage the event, even approaching school leaders to shut it down. The mayor denied this, but documents and emails suggest otherwise.

Morales entered this meeting not as a protester, but as a citizen frustrated by obstruction, delays, and silence. And for that, she was silenced. Her removal was the climax of a meeting thick with political tension. Her actual “violation” was speaking inconvenient truth at an inconvenient time.

Councilwoman Mary Springowski—typically forceful on decorum—remained silent. Others followed suit. There was no effort to de-escalate, clarify, or re-invite Morales to finish her remarks. The precedent was clear: if you challenge power, you risk removal.

Legally, the removal is suspect. In Norwell v. City of Cincinnati, the U.S. Supreme Court warned against punishing citizens for peaceful expression in public forums. In Nieves v. Bartlett, the Court held that retaliatory actions based on viewpoint discrimination are unconstitutional. Morales’s conduct was protected speech.

Instead of preserving order, the council abused it. Instead of protecting speech, they punished it.

II. Petty’s Trespass: A Convenient Enforcement

Weeks earlier, another troubling enforcement action took place. Local journalist and activist Garon Petty was criminally charged with trespass and disorderly conduct—not during a council meeting, but after attending a meeting of the Morningside HOA where multiple city officials, including Mayor Bradley and council members, were present. Petty, who has a history of watchdog reporting on city affairs, questioned whether this gathering violated Ohio’s Open Meetings Act.

Instead of addressing the legality of the meeting, officials had him removed—and later charged. According to court records from Lorain Municipal Court, Petty is now fighting formal criminal allegations for simply being present at a quasi-public event involving public officials.

Petty did not interrupt formal proceedings. He did not shout. He did not threaten. He showed up, asked questions, and got removed. Then the city pressed charges.

Ohio Revised Code §2911.21 defines trespassing as knowingly entering or remaining on property without privilege or after being asked to leave. But if a quorum of public officials discusses public business—even in a “private” setting—it may constitute a public meeting. The Ohio Supreme Court’s ruling in State ex rel. Cincinnati Post v. City of Cincinnati established that open meetings cannot be disguised behind private doors.

Petty was attempting to ensure transparency. His removal—and criminal prosecution—sends a chilling message. Lorain’s leadership appears more interested in silencing criticism than examining compliance with the law.

In fact, Council President Joel Arredondo himself appeared to reference this exact situation later in the May 5 meeting. “If there's more than three council people attending, that is called a sunshine violation,” he said, invoking Ohio’s Open Meetings Act. The statement unintentionally highlighted the irony: the same quorum standard Petty was warning about was now being used—publicly—as a caution by the very council charging him with a crime.

It’s worth noting that the Morningside HOA meeting wasn’t trivial either—it involved discussions of a new city traffic light installation, clearly qualifying as public business. The event had been publicly advertised. And yet, no council member took minutes or live streamed the event to comply with the Open Meetings Act.

Meanwhile, Council members declined to attend a separate public crime town hall hosted by Councilman Tony Dimacchia, citing the same Open Meetings Act as a reason for not showing. However, legal guidance suggests that if council members attend such public forums and take notes (or record), they can still comply with the law. This inconsistency suggests that enforcement of Ohio’s Open Meetings Act is being used as political cover, not legal principle.

In truth, discussing crime rates and citizen concerns—especially in a public, pre-advertised event—clearly falls within the category of legitimate city business. Council members could have complied with OMA by attending, taking notes, and ensuring the discussion was archived for the record.

The meeting had ended. There was no disturbance. Yet officials wielded criminal charges like a club. This was not about keeping order. It was about keeping critics out.

III. “You Work for Us”: The Morales Ejection Senario

The tension in the chamber during Jayne Morales’s remarks did not erupt—it was engineered. The newly transcribed footage of the May 5 meeting reveals that Morales attempted to speak calmly, but was continually interrupted by Council President Joel Arredondo. “Point of order, Mrs. Morales, per our guidelines...” Arredondo begins, not once but multiple times, invoking procedural objections before she can finish even a full sentence.

Morales had prepared comments about the city’s absence from a public town hall on crime. Yet rather than allow her to make her point, Arredondo cut her off, citing rules prohibiting direct comments at council members. When Morales pushed back gently, the meeting was immediately recessed.

This singular control over public access to the meeting floor sends a dangerous message: dissent is not welcome unless it is choreographed. The full video reveals no shouting, no threats, and no escalation from Morales. Her only “offense” was addressing the council directly with frustration.

This incident cannot be viewed in isolation. The transcript shows Morales telling officers afterward that she was warned she could be banned from future meetings if she didn’t leave. “Morris and Failing said they couldn’t remove us. We could stay. But we would be charged with a misdemeanor... I wasn’t leaving. But they said if we didn’t we could be possibly banned from further council meetings.”

The idea that an elected body can ban a resident from attending future meetings over protected speech runs afoul of both the Ohio Open Meetings Act and First Amendment doctrine.

Not only was Morales removed—she was silenced in perpetuity under threat. That’s not law enforcement. That’s political suppression.

The conversation following her removal further exposes this coercive dynamic. “Now you have a legit criminal charge,” Captain Failing said. “If we walk out and sit in the parking lot, what happens?” Morales asked. “Nothing,” he replied. This proves the issue was never disruption—it was optics and control.

Morales was not physically threatening. She did not shut down the meeting. Yet the officers, guided by Arredondo’s lead, framed her exit as the easiest path—for them, not for her rights.

This is how suppression operates in subtle tones. Arredondo played the enforcer inside chambers. The police played the persuaders outside. The result? A citizen was muted.

IV. Selective Enforcement of the Open Meetings Act

The events surrounding the Morningside HOA meeting and Councilman Tony Dimacchia’s town hall on crime have ignited concerns over the selective application of Ohio’s Open Meetings Act (OMA) by Lorain’s city leadership. What the public witnessed in both cases wasn’t just inconsistency—it was evidence of political convenience disguised as legal interpretation.

At the Morningside HOA event, at least three public officials were present: the mayor, the city safety service director, and a city council member. These weren’t just social attendees. The meeting included discussion of a new traffic crossing light being installed on city property—an action squarely within the scope of public business. By definition, that gathering constituted a meeting under the OMA, which mandates that when a majority of a public body convenes to discuss city matters, it must be open to the public, noticed in advance, and recorded.

But that didn’t happen.

There was no public notice. No minutes. No transcript. No public accessibility. No acknowledgment of the meeting in city records. In short, the city violated the letter and spirit of the OMA—and no one in government seems interested in accountability.

Contrast that with the town hall organized by Councilman Dimacchia. The meeting, held at a school auditorium, was publicly advertised on flyers, social media, and the city’s own community channels. Its purpose? To discuss crime and public safety—pressing concerns in Lorain. Yet, despite this openness, multiple council members and department heads refused to attend. Their excuse? That doing so would constitute a “public meeting” requiring OMA compliance.

Council President Joel Arredondo explicitly stated that three or more council members attending would trigger the OMA and put the city at legal risk. This interpretation, while technically correct in structure, was weaponized as a reason not to engage with constituents. The OMA does not prohibit officials from attending public events. It merely requires that if public business is discussed among a majority, it be noticed and documented. Even then, a solution existed: show up, record the meeting, and publish the transcript.

Instead, city leadership selectively applied the law to justify absence while simultaneously ignoring it when it came to closed-door gatherings like the Morningside meeting. This isn’t about legality—it’s about intent.

Mayor Jack Bradley, in defending his absence from the town hall, claimed he had a prior commitment with the Ohio Mayors Alliance. He also asserted he wasn’t included on the agenda. Dimacchia refuted that claim on the record, saying the mayor was invited in the very first outreach. “You did not respond to that email,” he said. “You were in fact invited.”

Dimacchia went further, accusing city officials of attempting to get the town hall canceled by pressuring Lorain City Schools, falsely citing ethics violations and conflicts of interest. His impassioned remarks made it clear: this wasn’t a scheduling conflict—it was political sabotage.

In both meetings, public business was at stake. In both, quorum-level participation was either reached or anticipated. But only one received scrutiny, and only one was avoided.

This is the hallmark of selective governance. When laws are enforced inconsistently, they cease to function as laws and become political tools. The OMA exists to promote transparency, not block engagement. Lorain’s use of it to dodge accountability in one instance while flouting it in another betrays the very citizens it’s designed to protect.

The law doesn’t change based on who’s in the room. But in Lorain, apparently, the rules depend on the narrative.

V. “Just Leave”: The Quiet Coercion Behind a Forced Exit

The ejection of Jayne Morales from the May 5 council meeting didn’t end with the sound of a gavel. It continued in hushed tones in the back of the chamber and hallway, where Captain Failing and Captain Morris—two of the highest-paid officers in the city—made it clear that while Morales could technically stay, the consequences would escalate if she did. The exchange revealed that what was being enforced wasn’t law, but obedience.

In footage recorded by Morales and a companion, Morales is seen speaking to officers after being asked to leave the meeting. “They said if we didn’t [leave], we could possibly be banned from further council meetings,” she said. Captain Failing replied, “It’s easier for you to just leave... because now you have a legit criminal charge.” When asked if that meant a misdemeanor, he responded, “I have to double check.” Even as he admitted the low level of the charge, the implication was unmistakable: speak up and you’ll face consequences.

Morales asked the officers what she had done wrong. “What did we say that was so disrespectful?” she demanded. “They shunned us.” Failing admitted he didn’t know the exact basis for her removal, only that charges could result. “We’re just trying to give you guys the information on what will happen,” he added. That “information” amounted to a clear threat of criminalization.

At one point, Morales pressed further. “If we walk out and sit in the parking lot, what happens?” Failing replied candidly: “Nothing.” This statement is vital—it confirms that no ongoing disruption was occurring. The danger, if any, was entirely political. The officers weren’t maintaining order; they were facilitating the silencing of a critic.

Morales made a poignant observation: “When are we supposed to talk to council if we can’t talk at a council meeting?” The rhetorical question speaks to the heart of the matter. Council’s refusal to allow criticism during public comment, and the police's compliance with this suppression, has effectively revoked a fundamental democratic right.

This was not a heated protest. Morales wasn’t screaming, threatening, or being unruly. She was upset, yes—but her comments were grounded in policy concerns. The use of law enforcement to neutralize this dissent reveals a city government more interested in optics than constitutional principles.

Adding to the concern is the apparent threat of a ban from future meetings. While officers couched it as a possible consequence of disorderly conduct, the reality is that such a ban would be illegal. The Ohio Open Meetings Act guarantees every citizen the right to attend public meetings. A ban based on viewpoint or speech content would not only violate state law—it would raise federal constitutional concerns under the First Amendment.

Full Video of Morales being "threatened with Criminal Charges"

It is also worth noting the larger context. Captain Morris, who helped facilitate Morales’s removal, has previously engaged in online commentary critical of citizens who question city leadership, including a now-public post by Chief McCann that described critics as “unhinged.” These sentiments, shared by top brass, suggest a culture that conflates dissent with disorder—a dangerous precedent.

The video footage reveals officers appearing cordial, even sympathetic. But cordial coercion is still coercion. Morales was given a choice: comply and go quietly, or risk arrest for a low-level misdemeanor. The enforcement wasn’t about keeping order—it was about protecting egos.

And this is precisely where the law intervenes. As detailed in the legal analysis below, such conduct likely violated Morales’s civil rights.

⚖️ Legal Analysis: Was the Removal Lawful?

Jayne Morales’s removal from the May 5, 2025, Lorain City Council meeting raises serious constitutional and statutory concerns. Her case implicates both First Amendment protections and provisions of the Ohio Open Meetings Act (OMA), as well as state law concerning public meeting decorum and criminal disruption.

1. First Amendment Rights

Under City of Madison Joint School District v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Commission, 429 U.S. 167 (1976), and Norwell v. City of Cincinnati, 414 U.S. 14 (1973), citizens have a right to speak at public meetings during designated times without fear of viewpoint discrimination. Morales was not yelling, threatening, or cursing. Her speech—directed at the Council’s absence at a public safety forum—was squarely within the bounds of protected political expression.

The First Amendment does allow for “reasonable time, place, and manner” restrictions, but those must be applied neutrally and consistently. Selectively silencing Morales while allowing others to speak longer or more aggressively—as has occurred at previous meetings—could constitute viewpoint discrimination, which is unconstitutional.

2. Ohio Open Meetings Act (OMA) Violations

The Ohio OMA, codified in R.C. 121.22, guarantees the public’s right to attend meetings of public bodies and observe deliberations. Morales’s threatened ban from future meetings and the attempt to silence her comment arguably violate this statute. The Act requires meetings to be open and accessible, and restrictions on speech must be narrowly tailored.

3. Disorderly Conduct Statute: R.C. 2917.11

The officers implied that Morales might face a charge of disorderly conduct, a minor misdemeanor under R.C. 2917.11. However, Ohio courts—State v. Schwing, 42 Ohio App. 3d 113 (1987)—have held that peaceful, verbal criticism of officials does not meet the threshold for disorderly conduct unless it is loud, offensive, or incites violence. None of these conditions applied to Morales’s speech.

4. Criminal Disruption Statute: R.C. 2917.12

R.C. 2917.12 prohibits disrupting lawful meetings, but the disruption must be substantial. As reaffirmed in State v. Brand, 2023-Ohio-3290, the statute cannot be used to punish mere disagreement or unpopular speech. Morales’s brief comment did not halt the meeting or prevent its continuation in any meaningful way. Once council recessed, there was no active disruption.

5. Due Process & Retaliation

Threatening criminal charges or future bans without a hearing or formal finding constitutes a due process violation. Moreover, if the removal was motivated by Morales’s past criticism or affiliation with political opponents, it could also amount to retaliation, actionable under Nieves v. Bartlett, 587 U.S. ___ (2019).

VI. A Culture of Control: From McCann’s Posts to Council’s Silence

The broader context of Jayne Morales’s removal cannot be separated from the prevailing culture of intimidation and suppression that has taken root in Lorain city leadership. From the top ranks of the police department to the upper echelons of city hall, there is a demonstrated pattern of responding to criticism with condemnation, and to dissent with discipline.

At the heart of this culture is an attitude expressed bluntly in a 2023 Facebook post by Lorain Police Chief James McCann, in which he referred to local advocates as “unhinged” and suggested their opinions were a threat to the city’s image. While the post was later deleted, screenshots of it circulated widely—and its sentiment echoed through the conduct of officers like Captain Morris and Captain Failing, who, on May 5, used their authority not to protect peace, but to enforce political quiet.

When the highest-ranking officers in the city are dispatched to council meetings and their main task becomes ushering out a citizen for speaking critically—without incident, without profanity, without even a raised voice—the message is unmistakable: Criticism will not be tolerated.

City leaders have reinforced this message in word and deed. Council members who normally champion transparency and fairness went silent as Morales was removed. The mayor, in previous town halls, sidestepped questions about selective enforcement. Even those like Councilman Dimacchai, who courageously criticized the administration during the May 5 meeting, ultimately left the room without being formally dismissed—a breach of protocol that mirrored the very arbitrariness Morales was punished for.

The climate in Lorain is one where political disagreement is increasingly framed as disorderly conduct. Where calling out absences becomes cause for removal. Where a council president enforces rules selectively, and officers act not as neutral peacekeepers, but as agents of censorship.

There’s no official policy on silencing dissent—but the practice speaks louder than any ordinance.

The implications extend beyond this single meeting. They cut to the core of public trust. How can citizens feel safe participating in democracy when participation itself becomes punishable? How can critics of city policy engage without fear of retaliation or criminal citation?

Jayne Morales’s experience is a warning. Not just about one meeting, but about the normalization of suppression. If Lorain is to be a city that values democracy, it must value dissent. And it must stop treating disruption statutes as tools of political control.

Lorain’s leaders cannot hide behind procedural pretexts or pretend neutrality. Not when the pattern is so clear. Not when the message is so chilling.

VII. Final Thought: A Pattern of Suppression, A Moment for Course Correction

What happened at the May 5 council meeting wasn’t an isolated failure—it was part of an escalating pattern of silencing dissent, dodging accountability, and weaponizing both procedure and law to suppress civic participation. When the rules are bent for allies and enforced like a hammer against critics, democracy becomes theater—and public trust evaporates.

Councilman Tony Dimacchai deserves credit for standing up during the meeting to criticize the administration for undermining the town hall. His speech was impassioned and necessary, and he rightfully called out a city apparatus that seems more concerned with optics than engagement. But his departure from the meeting before it adjourned was problematic. Symbolic or not, it broke council protocol and arguably left his constituents without a voice when they needed it most. Leadership isn’t just about making a statement—it’s about standing firm in uncomfortable moments.

Video of Tony Dimachaais Fiery Rebuke of Mayor Bradley

Council President Joel Arredondo’s refusal to allow Morales to continue speaking—despite her remaining civil—was a clear example of overreach. Worse, his decision not to read the letter from the police department aloud (a letter that may have included critiques or support) reveals a pattern of shielding the powerful from scrutiny while exposing citizens to punishment.

Mayor Bradley’s speech defending his absence from the crime town hall was also telling. He emphasized being at a scheduled event in Columbus, yet offered no solution for city representation at a major local forum. His comments about not being involved in the agenda and not receiving a formal invite were undermined by Councilman Dimacchai’s on-record remarks confirming that invitations were sent. Bradley’s explanation reads more like backpedaling than leadership.

Furthermore, whether or not the town hall or the HOA meeting constituted official public meetings under Ohio’s Open Meetings Act, the spirit of public service demands that elected leaders show up. These weren’t secret gatherings—they were advertised, attended by residents, and discussed urgent city matters like crime and public infrastructure. Leaders should have attended, noted the discussion, and ensured transparency, even if only three or four council members were present. There were lawful ways to comply with OMA—citing it as an excuse for political avoidance was dishonest.

This entire episode reinforces that council rules are not being applied fairly. Citizens like Jayne Morales are threatened with criminal charges for minor disruptions. Others are granted extra time without explanation. Still others are ignored or stonewalled entirely. Meanwhile, officials who disrupt meetings or dodge responsibility face no consequences.

What’s most alarming is the tone from law enforcement: “You now have a legit criminal charge.” “It’s easier for you to just leave.” These aren’t the words of public servants—they’re the phrases of enforcers working to silence political opponents.

Lorain deserves better. It deserves leaders who attend, who listen, who apply rules evenly. It deserves a police department that doesn’t act like a political security detail. And it deserves citizens like Jayne Morales, who speak up even when the cost is high.

If this council wants to rebuild trust, it needs to stop silencing critics and start listening to them. The future of civic discourse in Lorain depends on it.